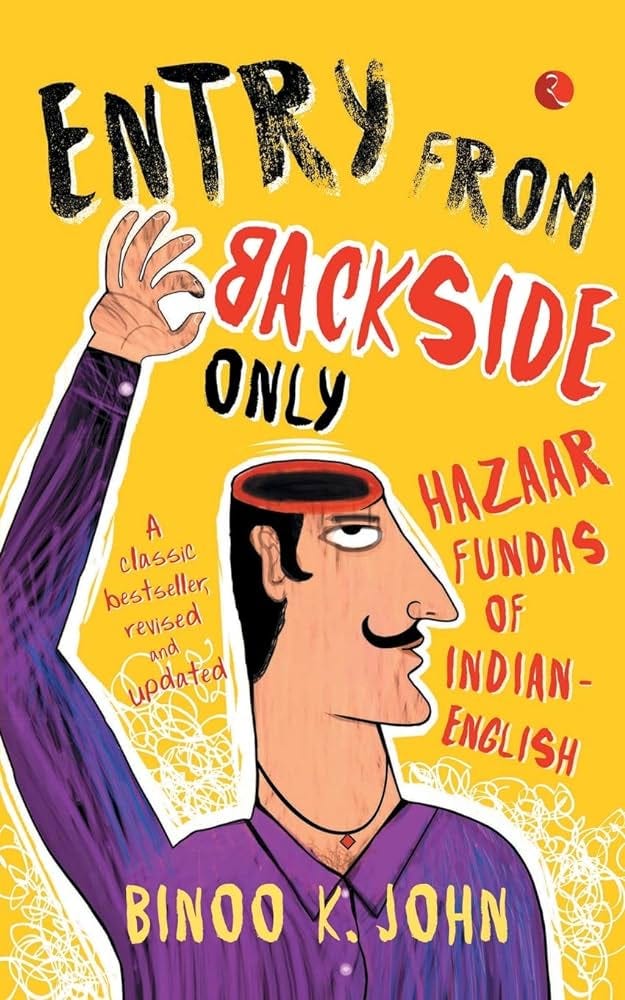

“Entry from Backside Only” by Binoo K. John

A book about Indian English and the multitudes it houses.

A book about language can take many forms. It can be the drab garb of a grammar book- prescriptive and academic. Or it could be the incisive sociocultural take on the many facets that a language holds outside its grammar rules.

This book is of the second type and it certainly rules.

I often tell my students that they ought not to judge themselves by the quality of English they speak. This often comes up, especially concerning what is the ‘right’ way to say, pronounce a word, or intonate an utterance. More often than not I remind them that in one way or another, more people speak some sort of English in the metropolitan streets of any major Indian city than in the whole of the British Isles put together.

Numbers rule in the end, isn’t it? (See what I did there, question tag most dearest?)

Behind every Backside is a Beatitude

I often ascribe my English not just to the foreign country I was brought up and educated in but also to the big Yellow Bible (yup, the Good News one) which my mother prescribed to me almost as early as I could read and her rule that with breakfast I must read the Bible for fifteen minutes every day. I do wonder whether this is where my reading discipline came from, after all.

One of my favourite Bible verses is the Beatitudes. To deconstruct a beatitude for its formulaic simplicity is quite easy. Let me demonstrate-

“Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

The form is simple-

“Blessed are ______________: for theirs is ___________”

Go on, you can form beatitudes of your own. Here’s mine-

“Blessed are the poor in English: for theirs is ample learning opportunities.”

For real. This book helped remind me how the gusto and innocent joy in which English is spoken and misspoken in many ways in my country gives opportunities for far more learning than the well-intentioned iambic pentameter of a cosy London countryside ever could.

Besides, the comic relief is in plenty and there is a “vas deference” in the types of Indian Englishes one could find.

Our Language Shapes Us

This book strengthened the notion that India is a country of regular upward social mobility and that English is often seen as the vehicle to achieve that ascent. While recent local flavours may seek to do away with everything English, the job market and the libraries of the world keep reminding us that this foreign tongue is now important for foreign remittances.

More than that, the chapters on film, culture, and politics really breathed life into the book. I bought it to learn of some mannerisms of Indian-English, that which the Nissim Ezekiels and Keki N Daruwalas of my literary education had forever imposed. But what I found was a treasure trove of quotes and sources. The sheer detail did exhaust me at times, but the steady evolution of this uniquely dynamic ‘variety’ (for that is the technical name) of this language did leave me pleased.

There are many entries into reading this book, but just the one for subscribing to this newsletter. The above button. Do oblige. I leave you with my favourite poem on Indian English. The metaphor is over the top, yes, but the imagery stays with you-

The Mistress

by Keki N Daruwalla

No one believes me when I say

my mistress is half-caste. Perched

on the genealogical tree somewhere is a Muslim midwife and a Goan cook. But she is more mixed than that.

Down the genetic lane, babus

and professors of English

have also made their one-night contributions.

You can make her out the way she speaks;

her consonants bludgeon you;

her argot is rococo, her latest 'slang' is available in classical dictionaries.

She sounds like a dry sob

stuck in the throat of darkness.

In the mornings her mouth is sour

with dreams which had fermented during the night. When I sleep by her side

I can almost hear the blister-bubble

grope for a mouth through which to snarl.

My love for her survives from night to night,

even though each time

I have to wrestle with her in bed.

In the streets she is known. They hiss when she passes,

Despite this she is vain,

flashes her bangles and her tinsel;

wears heels even though her feet

are smeared up to the ankles with henna.

She will not stick to vindaloo, but talks of roasts, pies, pomfrets grilled.

She speaks of contreau and not cashew arrack which her father once distilled.

No, she is not Ango-lndian. The Demellos would murder me if they got scent of this,

and half my body would turn into a bruise.

She is not Goan, not Syrian Christian.

She is Indian English, the language that I use.